“Sow a thought, and you reap an act;

Sow an act, and you reap a habit;

Sow a habit, and you reap a character;

Sow a character, and you reap a destiny.”

― Samuel Smiles

In their nature, habits are something different from other parts of personality. They are patterns through which the parts of personality and corresponding behaviors are being expressed.

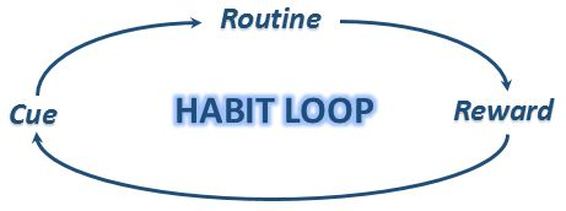

In his great book “The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do, and How to Change,” Charles Duhigg reveals the details about the scientific research that has led to a very important discovery: the so-called Habit loop (see figure below).

Sow an act, and you reap a habit;

Sow a habit, and you reap a character;

Sow a character, and you reap a destiny.”

― Samuel Smiles

In their nature, habits are something different from other parts of personality. They are patterns through which the parts of personality and corresponding behaviors are being expressed.

In his great book “The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do, and How to Change,” Charles Duhigg reveals the details about the scientific research that has led to a very important discovery: the so-called Habit loop (see figure below).

Every habit has three components: a cue (trigger), routine and reward.

A cue is anything that triggers the habitual routine. There are five types of cues:

If the routine brings a concrete reward to the person, it could be repeated. In that case, it would continue to repeat and reaffirm itself due to some sort of reward at the end.

The reward is usually an inner state of contentment or relief that comes through the routine itself, but can also be an external pleasant event or thing.

For instance, let’s say a particular alcoholic is triggered to have a drink by his inner feelings of loneliness, depression, or other kinds of negative emotions. An urge for relief appears at an often subconscious level. Initially, heavy drinking seems successful in its role as a depression-suppressor. Over time, his mind is trained to believe that alcohol brings the reward of defeating or forgetting the negative state of mind. The urge for a temporary relief has been satisfied. Heavy drinking then becomes a routine, reinforcing itself by getting a temporary reward again and again, despite the unpleasant and harmful mental or physical consequences afterwards.

In a way, every element of our psyche is a kind of habit. They are each being triggered by some internal or external cue, then run as a usual behavior, and, in the end, we get some kind of reward. So, it would be difficult to transform or remove any element of personality whatsoever, without first getting into the nature of habits themselves.

How is it possible to stop a negative habit, or change it into a beneficial one?

In Duhigg’s book, the results of his research show that habits are very difficult to remove—if not impossible—due to the neurological pathways that each habit establishes. Supposedly, these paths can’t be eliminated, so the corresponding habits can’t be, either. They can only be changed.

Duhigg points out: “How do habits change? There is, unfortunately, no specific set of steps guaranteed to work for every person. We know that a habit cannot be eradicated—it must, instead, be replaced. And we know that habits are most malleable when the Golden Rule of habit change is applied: If we keep the same cue and the same reward, a new routine can be inserted.”

In accordance with Duhigg’s conclusions, the path for replacing habits is to determine all three elements of the habit’s loop, and then to replace the routine. Here is the procedure:

1. Identify the routine. What’s the thing you want to work on?

2. Identify the reward. As the reward creates an urge or craving which drives the routine, you should try to feel and determine the root urge and, based on that, isolate the reward.

You must be meticulously careful in this process, because you could easily delude yourself and come to a wrong conclusion. Test each of your assumptions on a potential reward. Try out each reward in real life a few times and honestly examine whether you still feel the urge for that routine or not. If you do, that’s not the real reward, so try something else. As Duhigg says, “the reward does propel the habit only if you do not feel the urge to do the routine anymore.”

3. Identify the cue (trigger). To do this, examine which of five possible types this particular trigger belongs to. Once you isolate its type, use corresponding questions to get more information:

4. Make a plan for changing the habit. Which positive routine could replace the existing unwanted one?

However, there are additional ways to deal with habits which—I might dare to say—can remove them completely.

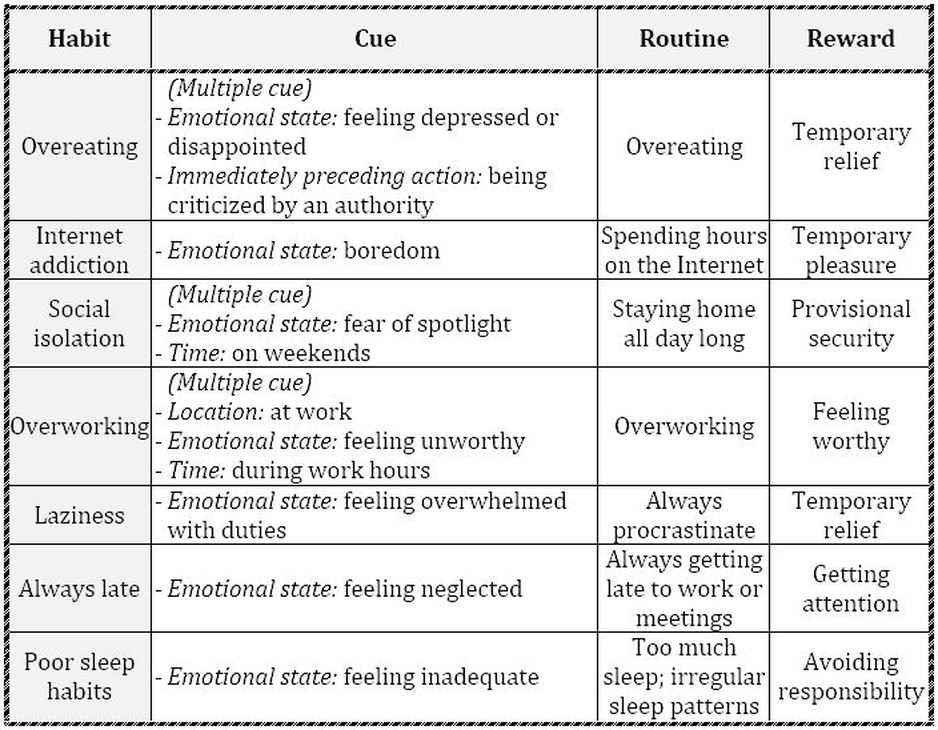

First, I would recommend that you make a list of all your habits, especially the unwanted ones. That list should include information on the cue, routine and reward for each habit. We will call it the list of habit loops.

You may take a look at such a list created by Marta, one of my acquaintances. She had a lot of self-destructive habits, and she spent some time trying to determine all the elements of the habit loops (see table below).

A cue is anything that triggers the habitual routine. There are five types of cues:

- Location (when you get to a particular place, the habit is triggered),

- Time (the habit is activated at a particular time of the day),

- Emotional state (for example, if one feels depressed, the habit of overeating is initiated),

- Other people (the habit is triggered if you find yourself in the presence of a particular person),

- Immediately preceding action (a specific action done by you or another person which then triggers the habit).

If the routine brings a concrete reward to the person, it could be repeated. In that case, it would continue to repeat and reaffirm itself due to some sort of reward at the end.

The reward is usually an inner state of contentment or relief that comes through the routine itself, but can also be an external pleasant event or thing.

For instance, let’s say a particular alcoholic is triggered to have a drink by his inner feelings of loneliness, depression, or other kinds of negative emotions. An urge for relief appears at an often subconscious level. Initially, heavy drinking seems successful in its role as a depression-suppressor. Over time, his mind is trained to believe that alcohol brings the reward of defeating or forgetting the negative state of mind. The urge for a temporary relief has been satisfied. Heavy drinking then becomes a routine, reinforcing itself by getting a temporary reward again and again, despite the unpleasant and harmful mental or physical consequences afterwards.

In a way, every element of our psyche is a kind of habit. They are each being triggered by some internal or external cue, then run as a usual behavior, and, in the end, we get some kind of reward. So, it would be difficult to transform or remove any element of personality whatsoever, without first getting into the nature of habits themselves.

How is it possible to stop a negative habit, or change it into a beneficial one?

In Duhigg’s book, the results of his research show that habits are very difficult to remove—if not impossible—due to the neurological pathways that each habit establishes. Supposedly, these paths can’t be eliminated, so the corresponding habits can’t be, either. They can only be changed.

Duhigg points out: “How do habits change? There is, unfortunately, no specific set of steps guaranteed to work for every person. We know that a habit cannot be eradicated—it must, instead, be replaced. And we know that habits are most malleable when the Golden Rule of habit change is applied: If we keep the same cue and the same reward, a new routine can be inserted.”

In accordance with Duhigg’s conclusions, the path for replacing habits is to determine all three elements of the habit’s loop, and then to replace the routine. Here is the procedure:

1. Identify the routine. What’s the thing you want to work on?

2. Identify the reward. As the reward creates an urge or craving which drives the routine, you should try to feel and determine the root urge and, based on that, isolate the reward.

You must be meticulously careful in this process, because you could easily delude yourself and come to a wrong conclusion. Test each of your assumptions on a potential reward. Try out each reward in real life a few times and honestly examine whether you still feel the urge for that routine or not. If you do, that’s not the real reward, so try something else. As Duhigg says, “the reward does propel the habit only if you do not feel the urge to do the routine anymore.”

3. Identify the cue (trigger). To do this, examine which of five possible types this particular trigger belongs to. Once you isolate its type, use corresponding questions to get more information:

- Location: ask yourself “Where am I?”

- Time: “What time is it?”

- Emotional state: “In which emotional state am I?”

- Other people: “Who else is here?”

- Immediately preceding action: “Which action directly preceded the need?”

4. Make a plan for changing the habit. Which positive routine could replace the existing unwanted one?

However, there are additional ways to deal with habits which—I might dare to say—can remove them completely.

First, I would recommend that you make a list of all your habits, especially the unwanted ones. That list should include information on the cue, routine and reward for each habit. We will call it the list of habit loops.

You may take a look at such a list created by Marta, one of my acquaintances. She had a lot of self-destructive habits, and she spent some time trying to determine all the elements of the habit loops (see table below).

Note that some of her habits were triggered by more than one cue.

Now, if you really want to erase a habit, you must remove all three components—cue, routine and reward. What should you do with each component? Here is my recommendation:

In one of his TED talks[i], psychiatrist Judson Brewer suggests that mindfulness can help us to break bad habits. Brewer describes an interesting idea in which you simply become curious and aware of your own routines. “Notice the urge, get curious, feel the joy of letting go and repeat,” he said. (You may notice that, in essence, this approach corresponds to our FA basic technique.)

One participant at the TED talk who was smoking was told, "Go ahead and smoke, just be really curious about what it's like when you do." After that, she said, "Mindful smoking: smells like stinky cheese and tastes like chemicals, YUCK!"

Anyway, the sheer power of the previous habit’s inertia sometimes is so strong that the habit eventually reemerges.

Related to that, Charles Duhigg adds another vital clue to this subject: “But that (‘the Golden Rule of habit change’) is not enough. For a habit to stay changed, people must believe change is possible. And most often, that belief only emerges with the help of a group.”

This leads us to the next vital element of our personality—the beliefs.

[i] https://www.ted.com/talks/judson_brewer_a_simple_way_to_break_a_bad_habit/transcript

Now, if you really want to erase a habit, you must remove all three components—cue, routine and reward. What should you do with each component? Here is my recommendation:

- Cue: Describe each trigger with a more detailed spectrum of concrete content. Do an appropriate Reintegration technique in order to transform it completely—Dissolving the Temporary I (DTI), Single or Double Chain (SC/DC), or the Inner Triangle (IT) technique.

- Routine: First, treat it in your mind with the Gentle Touch of Presence (GTP) technique; then, if possible, exercise the routine multiple times in real life mindfully, and for this you could use the Freshness & Acceptance (FA) technique.

- Reward: Since your reward is usually an emotional state, the best solution is to do the Inner Triangle (with coupling it with the cue, if possible), or Single or Double Chain technique. Of course, you can always try using the DTI instead.

In one of his TED talks[i], psychiatrist Judson Brewer suggests that mindfulness can help us to break bad habits. Brewer describes an interesting idea in which you simply become curious and aware of your own routines. “Notice the urge, get curious, feel the joy of letting go and repeat,” he said. (You may notice that, in essence, this approach corresponds to our FA basic technique.)

One participant at the TED talk who was smoking was told, "Go ahead and smoke, just be really curious about what it's like when you do." After that, she said, "Mindful smoking: smells like stinky cheese and tastes like chemicals, YUCK!"

Anyway, the sheer power of the previous habit’s inertia sometimes is so strong that the habit eventually reemerges.

Related to that, Charles Duhigg adds another vital clue to this subject: “But that (‘the Golden Rule of habit change’) is not enough. For a habit to stay changed, people must believe change is possible. And most often, that belief only emerges with the help of a group.”

This leads us to the next vital element of our personality—the beliefs.

[i] https://www.ted.com/talks/judson_brewer_a_simple_way_to_break_a_bad_habit/transcript